If ever it’s a good idea to say yes to being a guinea pig, it’s when agreeing to a trial that has never been used on humans before, courtesy of a technique pioneered by ‘Super Vet’ Noel Fitzpatrick. Especially if in doing so it could prevent your arm from being amputated because of injuries sustained during a catastrophic car crash. At least, so thought Mark Fussell in 2017.

The former Oxfordshire retained firefighter’s life was changed forever because of a single moment of distraction. Just a word of warning, some readers may find his story distressing.

On an autumnal day in October 2017, Mark was driving with the roof down in his two-seater sports car along his favourite stretch of the Oxfordshire Downs. Taking his eyes off the road to enjoy the view, he drove straight off the verge while doing 50mph. Before he had time to act, he nosedived into a ditch, going head over tail twice, then barrel rolling three times, before eventually landing a few hundred yards into the field.

“I remember every detail of it, every time my head hit the field, seeing great lumps of dirt fly up around me,” says Mark, who, amazingly, stayed conscious through the whole ordeal.

It was over in a matter of seconds.

“The pain was excruciating, off the scale, but it took me a while to process what had happened,” he says. “I didn’t realise a human being could put up with so much pain and stay conscious. I couldn’t breathe and I knew I was dying; I just sat there and knew this was only going to end one way. I was trapped in the car, which was smoking, and I just thought, how ironic, an ex-firefighter and I’m going to burn to death. And all I could think about were all the regrets of things I hadn’t done, and there was nothing I could do about it.

“Two women found me. I have no idea what the passage of time was like before they got there, but it probably wasn’t long. One stayed to talk to me and keep me conscious while the other ran to try and find phone signal to call for help.”

Before long, they could hear the sound of sirens.

“I remember hearing them discuss how long it would take to cut me out and put me on a spinal board, and a paramedic saying they didn’t think I had that long,” he says. “They said they’d give me something for the pain, but I just thought yeah right, death is the only thing to finish off my suffering.”

Mark was taken to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, where doctors managed to save him and he began what would be a lengthy road to recovery.

“I’d broken both wrists, several ribs and my sternum, and had punctured both lungs, as well as having whiplash and serious damage to my muscles,” he says. “They told me that I was lucky the field had been recently ploughed so the ground was softer, otherwise I would have broken my neck. I’d also knocked out several teeth, including my front one. My daughter and I have the same gap in our front teeth, and I just remember thinking how much it would upset her to see me dead with my tooth missing. So while I was trapped in my car I’d managed to wiggle it back into position, and my dentist was absolutely flabbergasted because it took root again.”

While one of his wrist breaks was clean, the other had been too badly damaged after getting trapped between his ribs and the steering wheel, and doctors told him they were going to have to amputate.

“That was a total disaster, because everything I do is hand related,” he says. “I’m an Antiquarian Horologist, restoring antique clocks and barometers for a living. Dexterity and sensitivity is everything to me, not to mention having two hands. I said to the surgeon, I’m a clock maker, this is my livelihood and my life, chopping off my hand is not an option. And he said, let me think about it.”

A few hours later, the doctor came back to Mark and told him about an experiment currently being trialled by some of his colleagues and a doctor in America, using a technique pioneered by Noel Fitzpatrick. He had worked out a method to fix injuries in dogs where significant damage had been done to the bones, using titanium mesh moulded to the gap, imbibed with chemicals to fool the bones into growing there. But it had never been tried on a human before.

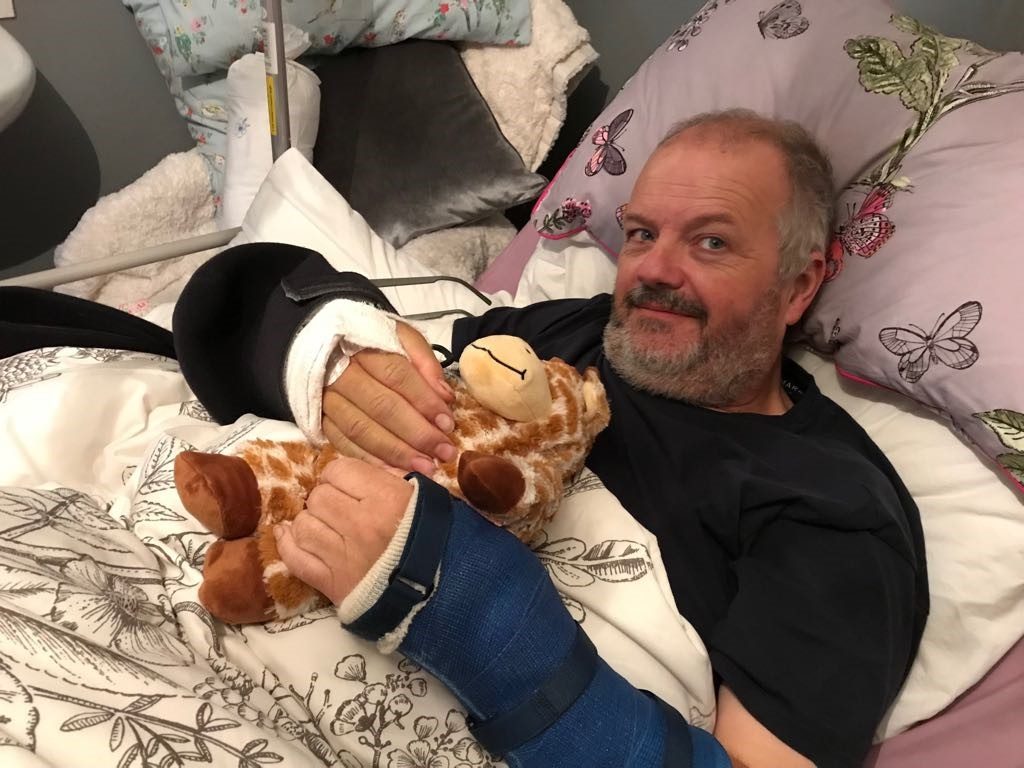

“I said yes, crack on, and unbelievably, it worked. By about the middle of January, I could feel it had joined up. I couldn’t tell you what the feeling was, but I just knew it. And a few days after yet another X ray, they removed nearly all of the 23 inches of plating from my arm, leaving one small bit in that wasn’t doing any harm. And I just got better and better.”

A former colleague suggested Mark reach out to Fire Fighters Charity to help him with his recovery. But he was sceptical.

“I’d been out of the fire service since 1992, and I thought they had better things to do than spend time with this silly idiot who’d gotten distracted looking at the view,” he says. “I thought it was a nice offer, but not for me, other people need it more than me, who are still serving and deserve it more. But then I came around to it, and thought, you’ve got nothing to lose. I spoke to a very helpful woman on the phone, who helped me complete my application because I couldn’t hold a pen or type. I told her everything that was wrong, and she said ‘I think they’ll enjoy you, you’ll be a bit of a challenge’. She was absolutely lovely, so helpful and encouraging, so I thought I’d give it a go.”

Within a few weeks, Mark was offered a place at Marine Court, our centre in Littlehampton.

“It was absolutely brilliant,” he says. “The NHS is fantastic, but you’re limited with the time you can spend with physios, and the charity is able to offer considerably more. One of the physios, Heather (who now works at Harcombe House) was so strong, pulling me all about in every which way, she was absolutely brilliant! I hope she doesn’t mind me saying so, because she’s tiny, but she could tear the legs off an ox!”

Like his fellow beneficiaries, Mark was given a personalised programme of activities tailored to his individual injuries, for which he enjoyed some gentle mocking from his peers: “You know what firefighters are like, they like to take the mickey. People were there with major injuries, completing whole body exercises, and I’m there sitting at a table bending my fingers up and down. But it was all so supportive and well-intentioned, meeting all of them was such a morale boost, not to mention the progress I made.

“I couldn’t open the doors round the centre when I got there, or my own car door. But by the end of the first week, I could do both. I could also look over my right shoulder again, which I couldn’t do before. I made such good progress that they invited me back for a second week to keep it going. I was wary not to overdo it, but everyone there gave you the courage to do the exercises, to know when to rest and know when to push yourself. It was great for putting your head in the right place because everyone was so positive and upbeat the whole time. I was pretty badly damaged, but there was no ‘we can’t do anything about that’ attitude from anyone. The attitude was to crack on and see what you can do. I just can’t think of a single negative about the whole experience.”

“I was pretty badly damaged, but there was no ‘we can’t do anything about that’ attitude from anyone. The attitude was to crack on and see what you can do.”

Mark Fussell

“I didn’t think I deserved the charity’s help. I was in this mess because of my own stupid fault, and worried I was taking a place from someone else. I wasn’t in the service for that long and I’d left so long ago, I find it hard to get my head around the fact the charity can still support me. Also, I’d never been somebody who had to ask for help. But instead of dwelling on that, I thought I just had to plough on. The more I chatted to people the less I worried and the more I concentrated on getting better and getting my independence back.”

Psychological therapists at Marine Court also kept a close eye on Mark, concerned he could have a delayed response to the trauma of the accident and that he could experience an emotional crash at any moment. But Mark had other ideas: “Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t ecstatic about my injuries, but I was just happy to be alive. I felt I should have been dead, so every second of every day was a Brucey Bonus. If you start thinking about life like that, it’s amazing what you stop worrying about. I’m generally quite a happy person and I have a good self-righting system. You can sink me as deep or as often as you like, but I always end up bouncing back.”

Mark did speak to the psychological team while at the centre, and they agreed that he seemed to be processing what had happened to him in the best, most healthy way that could be expected.

“I think because I remember every second of the crash, I’m not haunted by blanks or confusion,” he says. “I know exactly what happened: I stared death in the face and I got away with it. Also, the number of complete strangers who came together to support me had a hugely positive impact on me. All these lovely people who don’t know me from Adam, mucking in and helping me out. From the women who found me, to the emergency services who rescued me, the staff and beneficiaries of the charity. Even the members of the public who went to the crash site afterwards and helped retrieve everything that had fallen out of my car, including several thousand pounds worth of client repairs I’d been on my way to deliver. I still get emotional to think how much help I’ve received from ordinary people.”

On the first anniversary of the crash last October, Mark revisited the same road at exactly the same time of the afternoon that his car left the road.

“It was utterly bizarre being there, and I kept expecting to see myself coming over the brow of the hill,” he says. “I just feel so lucky, I could have left there in a mortuary van. But it wasn’t my time, and I’m using the experience to enrich my life and get more out of it. I find I enjoy life at a different pace, more in depth than your average person who gets up for work each morning and goes to bed at night, thinking it will go on forever. It doesn’t. These things can happen at any time. I had a full weekend planned, I was due to visit a customer and then see friends. It was a totally ordinary day until it wasn’t. Then wallop, all that just stops. To know these things can happen to anyone is a sobering thought, but it does make you enjoy life more.”

Thinking back to the regrets he felt in the immediate aftermath of the crash, Mark has also changed his attitude: “Since the crash, I’ve become a grandad, I’ve met someone new, and I’ve started to travel the world. You wouldn’t have caught the old me at concerts or gigs, but I go to live festivals and I love it. I’m back at work and happier than ever. The next time I lie there dying, I don’t want to have a great big list of regrets screaming through my head, I want to think, yeah I did it all. I had a great go.”

If you’re suffering with an injury or condition and would like some extra help, get in contact with us. Even if you’ve left the service like Mark had, as long as you spent five years in your role (or two if you were made redundant) you’re a beneficiary for life. That means we can support you for the rest of the life. So it doesn’t matter how long it’s been since you left, get in touch with us today and see if we can help. Contact our Support Line on 0800 389 8820 or enquire online.