Please note: the following story contains references to suicide that may be upsetting to some readers.

Walking around Glenrothes Fire Station in Scotland, almost everyone you meet will have a memory of Colin Speight – whether it’s one of their own, or one they’ve heard through a colleague. He was, and still is, central to life on station almost two years after his death.

From the “clown” and “joker” of the crew, through to a listening ear and comfort to anyone he worked with, Colin provided constant support and friendship to all he worked with.

Tragically, he took his own life in December 2021, at the age of 47. His death came as a huge shock to his crew, both at Glenrothes and Cupar Fire Station, where he also worked, as he’d shown very few signs that he’d been struggling in the months before.

We visited two of his closest friends and colleagues, Gordon Nimmo and John Ovenstone, at Glenrothes to hear some of their memories of Colin, and how they individually coped following his death.

Both Gordon and John have worked with us over the last few months as we’ve developed and released a suite of online suicide prevention and postvention resources and now – as we launch a 24/7 Crisis Line to combat fire service suicides – they hope by sharing their experiences, they’ll encourage anyone who’s suffering in silence to reach out. You can find out more about our Crisis Line here:

“Colin was always at the forefront of helping other people,” says Gordon. “You do this job as a firefighter to help other people, and Colin was doing that for the public, the community and his colleagues on shift.

“He set up a mental health board with posters, advice and all sorts of things. He was always out there to help other people, but I just think he didn’t help himself really.”

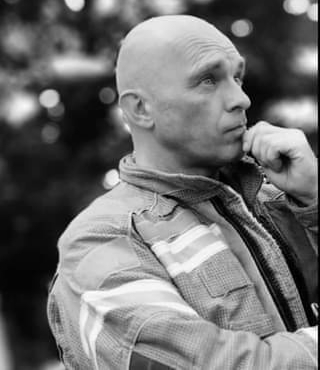

Colin passed away at the age of 47

Gordon was the first to find out about Colin’s death, and had to break the news to his mum, Margaret, on the day – something he says nothing could ever have prepared him for.

“Colin was due to come in on the day shift but he hadn’t shown,” says Gordon. “En route going home, our Watch Commander rung me and told me he hadn’t shown up, so I went past Colin’s mum and step-dad’s house because we knew he was staying there.

“While I was there, we were phoning the police because his mum hadn’t heard from him all weekend. The police van pulled up outside and they told me they’d found him…

“I had to go in and break the news to Colin’s mum. I never want to have to do that again… you deal with a lot of stuff in the fire service, fatalities and stuff like that, but you don’t have to deal with seeing your friend’s mum being told that they’ve found her son.”

In the days that followed, both Gordon and John describe feeling complete shock.

“You just sit there numb, absolutely numb. All the emotion in that situation just gets sucked out, you can’t believe it’s actually happened,” says John.

“Colin was always the rock and the joker of the group. That’s the concerning thing for us, we really didn’t see it. We knew he was going through some difficult times, but we always assumed he was alright because he was always alright on the surface.

“He was always having a joke and a laugh and he was always bubbly, never down, and it just shows with mental health it can really be a mask. It definitely needs to be brought forward that it shouldn’t be like that.

“Looking back, you wish that you’d picked up on the small signs that probably were there, but outwardly he looked so fine. It really was a massive shock.

“We miss him every day, you still expect him to walk through that door every morning and it’s still the same, for me anyway, you forget sometimes that it’s even happened – you expect him to come in and be his usual self. I think that’s the acceptance – it’s been a year and a half, and the acceptance still isn’t there.”

Gordon adds: “The initial period straight after it, it’s almost trying to comprehend it’s happened… his coat’s still on the peg, his gear’s still about, his locker’s still there.”

Both Gordon and John found comfort in talking and sharing with their colleagues, while keeping Colin’s memory alive day to day.

“Things move quickly in the fire service and we’re on different Watches now, but we’ll always have that bond with him,” says John. “If we’re out training or doing something and there’s a funny moment or whatever, Colin gets brought up like 95% of the time. He’d have loved what had happened.

“That’s a coping mechanism for me, and I think it’s a coping mechanism for all of us.”

Gordon and John have both browsed some of our suicide prevention and postvention resources, and fed into them as they were developed. You can see those here:

“Taking part in that was a massive realisation,” says John. “The way it’s structured is amazing, I think it’s a great piece that’s going to come into effect and I think it’ll help a lot of people.”

For Gordon, he’s found himself making small changes on station to ensure everyone feels they can talk and discuss how they’re feeling.

“I’m finding myself more now, when dealing with incidents that are quite traumatic, making sure that there’s things put in place for the crews that are involved in it – whether it’s dealing with a fatality, a suicide or a really bad accident,” he explains.

“They might have been fine straight away but there’s something further down the line that might trigger that and then it might tip them over the edge, so I’m making sure that people are fine now and that they’re well aware that we can refer them. There’s help there.

“I think the emphasis now is that you’re making sure you’re looking after yourself and your friends and colleagues – being proactive and doing something about it, rather than being reactive and waiting for something to happen, and then dealing with it afterwards.”

We also spoke to Colin’s mum, Margaret, and step-dad, Bill, both of whom have remained very close to Colin’s colleagues since he passed away and have found great comfort in those friendships.

Bill joined Gordon, John and a team of other personnel in completing a 96 mile walk in memory of his step-son, while raising an incredible £20,000 to be split between us and Survivors of Bereavement by Suicide (SOBS).

The group walked the West Highland Way in just five days, while wearing full fire kit and breathing apparatus.

“We found talking to each other our best coping mechanism at the time. We’ve hugely appreciated the help of the fire service, and the charity walk in particular was a huge help,” says Bill.

“It was one of the moments in my life that’s up there with the birth of your children… I remember shortly after the walk, a couple of the guys did another walk and we joined them.

“Our granddaughter, Colin’s daughter, and her mum were with us and we were walking along as a three. One of the guys behind was talking to his pals about difficulties he was having in his relationship.

Colin’s friends have remembered him as a constant support

“I said, ‘that’s your dad’s legacy’… the fact they were talking so openly to their colleagues, and getting it out of their system, that’s Colin’s legacy.”

Both Bill and Margaret are keen to help promote our new Crisis Line, knowing how vital it is for fire service personnel, both working and retired.

“We fully support all the work that the charity does and the projects it’s bringing out around mental health. If this helps just one person then that’s great,” says Margaret.

“The support and friendships we have made with many of Colin’s colleagues, some we knew and many we now know, have been equally supportive to us as a family. This is all very much appreciated, valued and will always be treasured.”

Margaret was offered a Family Liaison Officer through the fire service, shortly after Colin’s death, and she says they proved a huge support for months afterwards. They went on to get a second one, when he moved positions, and say he’s been equally as valuable to them – something they’re incredibly thankful for.

If you’re feeling suicidal, call our Crisis Line on 0300 373 0896.

If you feel you’d benefit from our health and wellbeing support, you can call our Support Line on 0800 389 8820, make an enquiry online or visit the ‘Access Support’ tab in My Fire Fighters Charity.